Weaving in Afrin

RUGS AND FLATWEAVES OF THE KURDS OF NORTHWESTERN SYRIA YASER AL SAGHRJI

"Show us something woven in Syria " . The frequency of this request set the author, an experienced rug dealer specializing in tribal kilims and textiles whose shop is close to the great Umayyad Mosque in the heart of old Damascus ,on a quest to discover the weavings of his native land . Here he looks at the work of the Kurdish weavers of Afrin , close to the Turkish frontier in northwestern Syria .

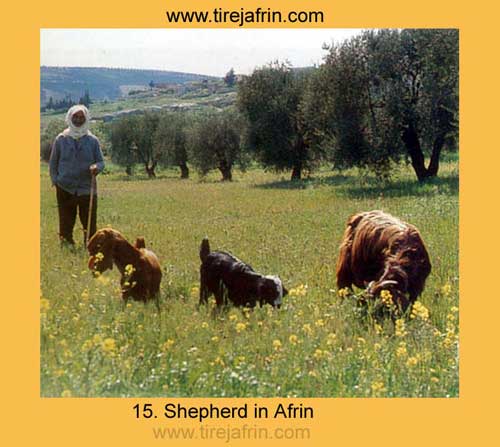

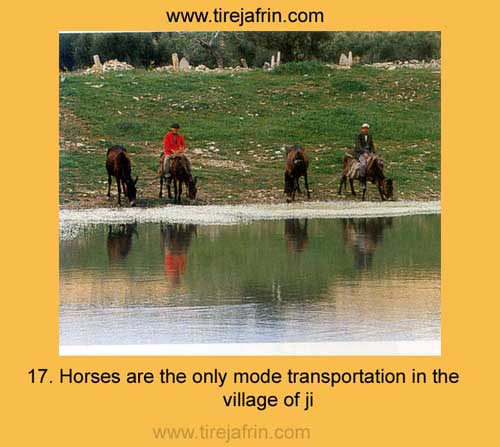

The Kurds of northwestern Syria have a long history . They arrived in the region in two waves : first Aryans who migrated from Central Asia in the 2 nd millennium BC , followed by Caucasians who came from the Transcaucasus during the 1st millennium BC . The term Kurdistan first appears on a 12th century map drawn up for the Seljuk Sultan Sinjar , when the region was placed under the rule of Suleiman Shah . But it was not until the late 16th century , under the rule of Sultan Mehmet 111, that the northern Aleppo region was included in the Ottoman province of Kurdistan . The major town in the area , some 60km northwest of Aleppo ,is Afrin , a name derived by Kurdish nationalists from ava riwen , a phrase meaning "murky red water " although the Sprian Geographical Lexicon suggests that it originates from afro ,an Aramaic word meaning fertile land .

The majority of the inhabitants of Afrin and the surrounding region are Kurds , of whom the older generation speak little Arabic . According to recent Syrian government estimates they number around 600,000,but the Kurds themselves claim a population in this area of over two million . They are part of an ethnic mix that also includes Arabs, Armenians (originally refugees from Turkey during the first quarter of the 20th century) , Turkmen and 'Qurbats' or Gypsies.

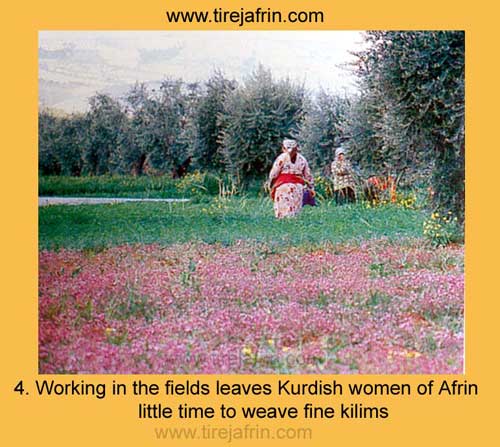

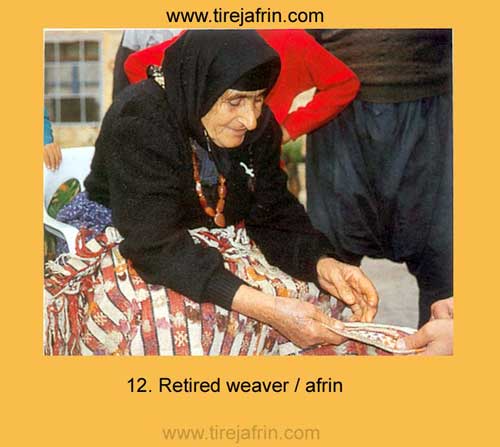

Most of the Kurds in this area are Sunni Muslims , although there also some Yazidis , who combine Islamic and Zoroastrian beliefs . In both appearance and to some extent lifestyle , the Kurds tend to be distinct . Kurdish women are normally the weavers ,but unlike Qurbat women who leave the home to earn the family bread ,Kurdish women only work in their homes or farms , and only with their relatives and friends . Unlike Arab women , however, Kurdish women are free to interact with male friends of the family . At times , even receiving male strangers in their homes when no men are present is acceptable , especially for elderly women .

The simplicity of their lives, their general state of poverty, and the long working day, has left the Kurds of Afrin little time to produce refined weavings. Only the wealthy pashas, or landlords, could afford to pay skilled weavers to make dowry or domestic articles. Today the continuing prosperity of such families means that they have no need to sell their heirloom textiles, and it is consequently very difficult to find finely woven pieces in the bazaars of Aleppo and Damascus. Most items produced by women and girls with limited resources, after a long day's work, are practical domestic items such as floor covers, guest blankets, cradle covers, wedding screens wedding bed covers, and prayer rugs.

In the 1970s, weaving all but came to a halt in the Afrin area. Alongside other economic and social factors, this was due to the fact that local products had none of the

characteristics demanded by a Western-led market – fineness, symmetry, and a muted palette. Hardship forced many people, particularly Kurds, to move to the larger cities of Aleppo and Damascus. They have not returned: today, when travelling through the area from September to May, the working months of the year, one sees hardly any young people. At the same time, of course , this meant that local styles of weaving have remained relatively isolated from market influences.

As a Syrian whose primary business in Damascus is selling kilims, I regularly receive requests from foreign visitors to see Syrian-made weavings. This has encouraged me to look for all types of textiles made within the borders of Syria, and the rare moments of discovery of quality pieces are particularly thrilling .

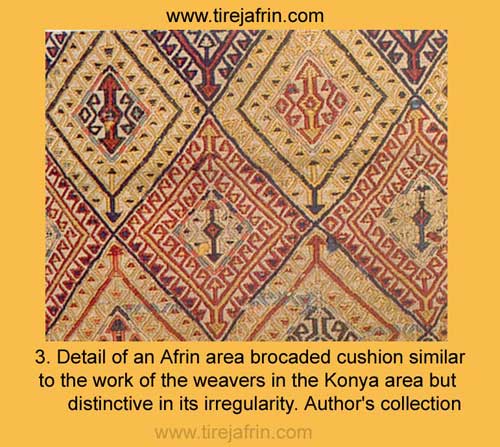

While wandering in the covered bazaars of Aleppo during the winter of 1997 and looking through piles of weavings, I was struck by a brightly coloured cicim fragment. With a variety of tiny designs, it looked too irregular to be of Turkish origin, despite its close resemblance to work produced by Kurds in westwrn Anatolia, especially Sivas cicims. The dealer admitted that it was made by the Kurds of Afrin, and said that I could have it, adding that it was not a particularly good example.

Back in the hotel, my interest in the piece began to escalate and I couldn't wait until the next morning to go back to the bazaar to look for more fragments, or better still a complete cicim. I found only one dealer who carried such pieces, and it was with some reluctance that he introduced me to his supplier, who turned out to be a well-known and respected member of the Kurdish community. He was later of great help to me and acted as interpreter when I visited Afrin.

Kilims and other flatweaves from this area, unlike their counterparts in Turkey and Iraq, are purely functional and have much in common with other types of domestic weavings that were until very recently untouched by the market, such as the gabbehs of southwestern Iran and North African Berber weavings.

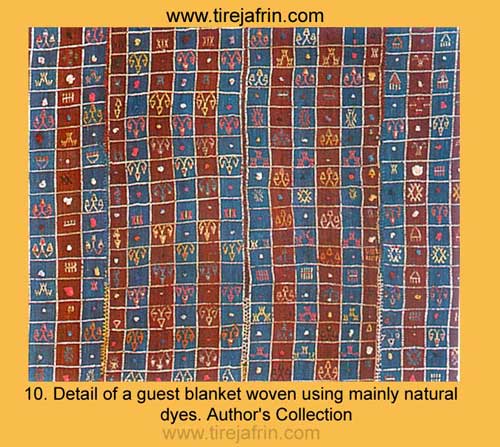

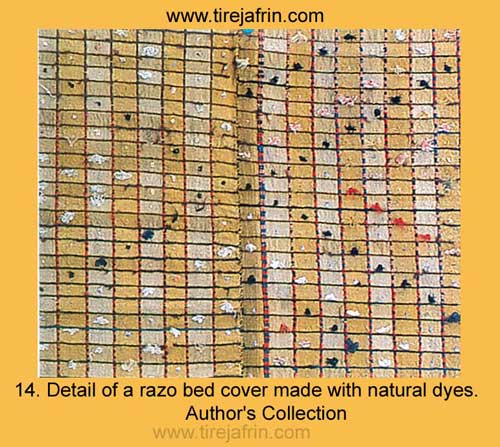

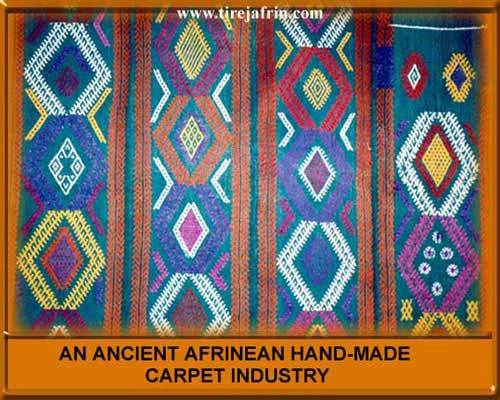

Their bright intense palette is their most striking feature. Typically they are made using the strongest colours available, including the bold yellow, green and red used on the flag of the only independent Kurdish state to date, the short-lived (1945-46) Soviet-backed Mahabad Republic. Orange occurs more often than any other colour even though, lacking a specific term, the Kurdish language embraces it under the general designation of zare, yellow. In general the dyes in Afrin kilims are of poor quality, and bleed frequently. Occasionally one may find a piece with truly pleasing colours, but this is very rare, and to date I have been unable to find a single example with purely natural dyes.

The Kurds, as well as other inhabitants of the region, began to use commercial chemical dyes during the late 19th century. These were supplied by a boyaci or itinerant jewish dyer, who travelled from village to village with his store of powdered dyes. He was considered a kind of magician by the villagers, who would provide him with accommodation, and pay for his services with foodstuffs such as olives, olive oil, bread, or at times a quantity of yarn. A woman in poulu once told me, however, that her family still used traditional natural dyes because they couldn't afford the services of the Boyaci. Instead they would place the wool along with pomegranate peel in the mud of a dried up well and leave it for four days, by which time it would be a brownish yellow colour. They also sometimes used

walnut skins to achieve different shades.

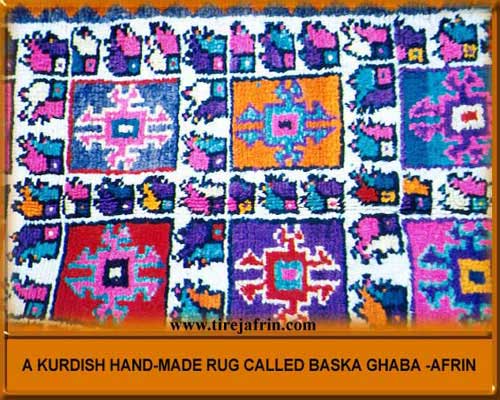

Weavers in Afrin produce four main types of textile: coarsely knotted-pile carpets ,

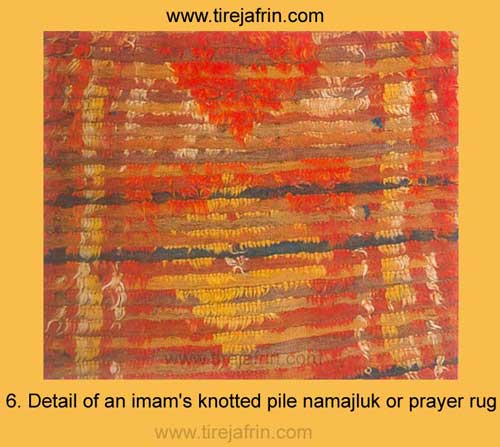

felts, slit-tapestry weaves and weft-float brocaded cicims. The first of these, pile rugs, are rare. In his 1988 overview of Kurdish rugs, An Introduction to Kurdish Rugs and Other Weavings, William Eagleton commented that he had not found any pile rugs that were definitely attributable to the kurds of Syria. Even so, from time to time I have come across small prayer mats (namajluks), generally woven for the local imam and used in village mosques. In the village of Kastalekuchuk I met Fahmih, who told me she had woven one of the rugs I purchased from a mosque. While coarse, these namajluks can be very attractive. They are sometimes knotted with unspun wool and rarely show any decoration. The second group, felts, generally made in a long, narrow format, are again of very coarse quality. They are dyed on completion of the felting process.

Afrin slit-tapestry weaves are similar to Rashwani and Reyhanl1 kilims from the neighbouring parts of southeastern Anatolia. Sometimes referred to as Reyhanl1, they share the same designs and have a similar overall appearance, but are much coarser and of poorer quality than their Turkish counterparts. Their local name, epoghajeh or 'hanged man' , refers to the vertical loom on which the kilims were woven. They do not have great market appeal and their format is not well suited to the modern Kurdish home, so they tend to be cut up or put to rough use. Very few have survived.

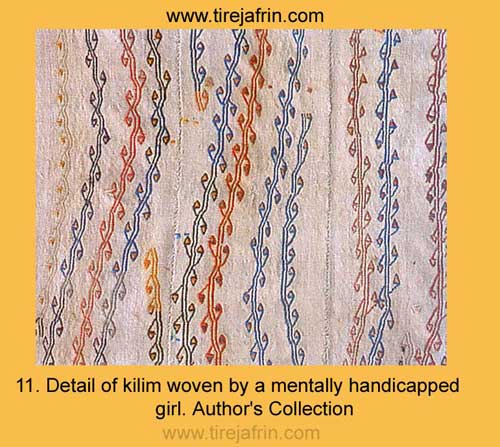

The final type of local weave is the 'cicim' , which features weft-float brocading on a balanced plainweave ground.

Pieces made in this way are normally constructed from narrow bands sewn together to form a larger textile. The bands, known as taj, are sometimes cut from one long strip, in which case the whole cicim is in the same colour. Others are made from separately woven strips in different colours.

Cicims are normally either folded under and sewn down at the ends or have typical Kurdish braided fringes, knotted at the ends. This finish is normally found on finer items such as wedding kilims and prayer mats, rather than the commonly used orange sofrehs and blankets. Sometimes the bands have border designs.

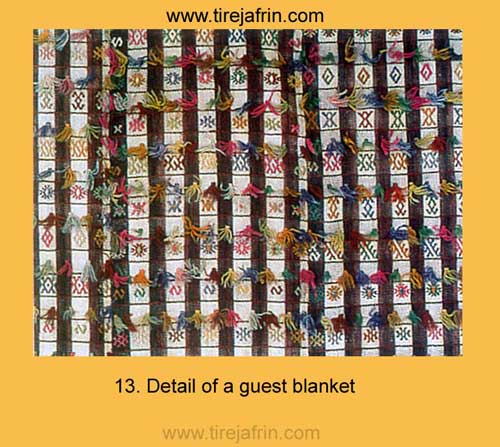

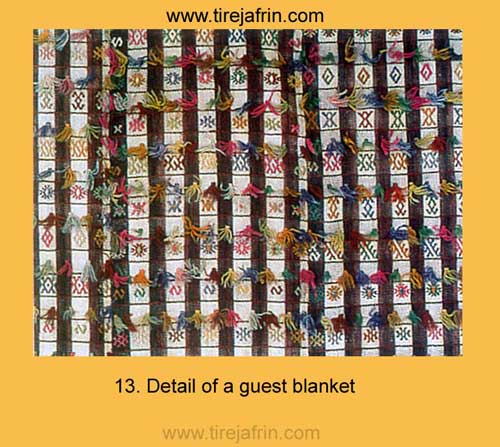

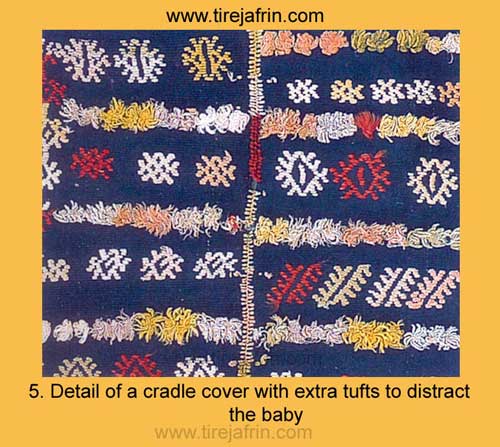

One very distinctive freature of these flatweaves is what the Kurds call paskul.

These are brightly coloured tufts of unspun wool, fragments of old clothing, silk, feathers or even human hair, perhaps with a talismanic function. It is a pre-Islamic tradition to attach such things to holy shrines or important possessions, and one that is still practiced today by many in the Middle East.

When questioned about the meaning of paskeul, Kurdish women tended to say that their purpose is "to scare flies and wasps away". Since they are often replaced by newer pieces, especially for weddings and religious festivities, paskul can confuse the issue of dating.

Flatweaves in the cicim technique were mainly intended for functional use and home decoration, some serving both purposes, rather than for the market. The simplest, and the most difficult to find, are the mooris. These striped plainwoven, jajim-like covers are normally found in brown, black and cream, and are the only type one would find being used on the floor today. They are very similar in some ways to Bedouin kilims.

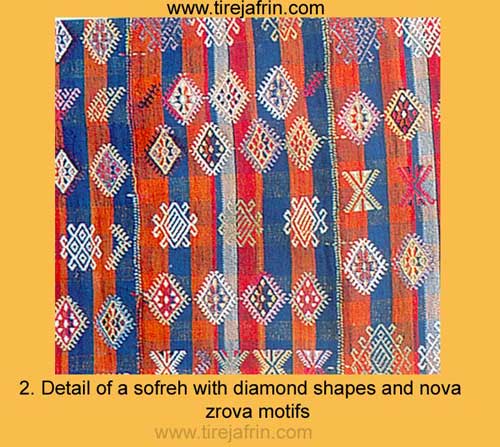

The second most common type are the sofrehs (2).Normally squarish in shape, the measure roughly 1.60 x 2.00m ( 5'3" x 6'7" ). Unlike Persian sofrehs, which serve as 'trays' for food , these are also used to sit on.

Most are made up of three taj (bands) without peskulk or fringes, and are very moderately ornamented. They are most commonly found in all shades of orange, but occasionally also in other colours such as green and red.

Blankets, chilay be chaeen, are very similar to sofreh but are generally slightly larger, more highly ornamented and of a more refined quality. They can also have fringes at the ends and border designs on the edges, but the most obvious feature is the addition of peskulk. The blankets are often of a single colour, although they can also be chequered.

Similar to blankets but smaller are cradle covers (5,20), saradargush. Measuring about 0.90 x 1.60m (3'0" x 5'3") , they consist of two or three bands and are generally attractive and more difficult to find. I was shown how they are used with the right side towards the baby, in which case the peskulk help to amuse the child. Prayer kilims, namajluks, are effectively saradargush without peskulk. As mentioned above, prayer rugs may also be of knotted pile.

Of all the types of kilims from this area, the most interesting are the wedding kilims. I have identified two types, the bar and the berda-peh. The bar is most commonly made up of three bands, the outer two – and occasionally all three – being of the same colour. I have seen examples featuring the following colour variations in the bands: two blue and one red, two red and one blue, one black and two red, one white and two orange, three orange, and finally three chequered bands. All came with fringes at the ends and were used to cover the mattress of the newly-weds in the early stages of their marriage, and on special occasions. They are of very fine quality, if not the finest in the area, and are carefully preserved by their owners. Families will only sell them in case of real financial need, so they are very difficult to find and are highly valued.

The other type, the berda-peh or screen (cover), are cheerful looking pieces, most but not all quite finely woven. They are generally pieced from six to nine different coloured bands (Kurdish women sometimes refer to them as taj taji, meaning band by band ). By tradition the berda-peh is woven by the mother of the bride, although occasionally a wealthy family will delegate the task to a highly reputed town weaver. During the wedding ceremony – which can sometimes last for several days – the screen is displayed behind the wedded couple. It is then used as a room divider to separate the newly married couple from the rest of the family. These pieces are then stored away, rarely in ideal conditions, or lent to poorer couples. Eventually the kilims will be reused to cover the coffin of a deceased family member on the way to the mosque. The imam then has the authority to sell the piece and donate the money on behalf of the deceased person's soul.

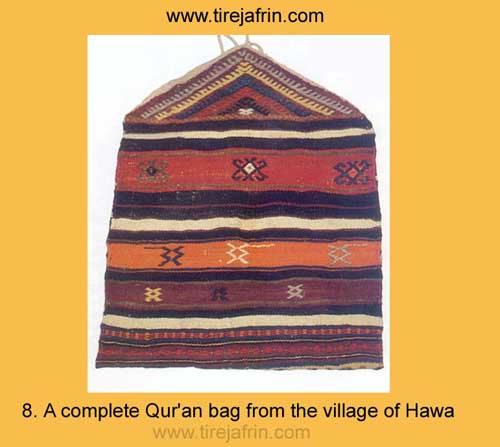

One can also find other types of flatweaves such as bags, including saddle bags. One rather unusual type is the kaj, a narrow band about ten centimeters wide and up to three metres in length that is hung across an arch or several arches, for guests to hang their coats. These are not common, and it was only after searching in thirteen villages that I located one. I have no doubt additional types of Afrin flatweaves will eventually be identified. It is not easy to uncover the meaning of symbols used in the kilims of this region. The language is all but lost, and weavers are generally able to shed little light on the meaning of the traditional motifs they are copying. The most common of all designs is the diamond shape, Which is present on almost all the pieces I have encountered. A variety of

other symbols may appear inside the diamonds. From What I was told, it seems likely that the diamond guards against the evil eye. Other motifs to the weaver's world, among them the nova zrova or the slim waist of a goats, water, the climbing vine, the urzak - a triangular shape with pendant forms representing a type of plant found in almost every home in the area. It is likely that while some symbols are talismans, others express ideas of prosperity on beauty, but more needs to be done on this aspect of Kurdish weaving. Today the situateion in Afrin echoes that found in many traditional Middle Eastern weaving areas. The future of these pieces is in danger for they are no longer being woven and the weavers of the past have not passed on their weaving skills to the next generation.

this article is taken from : Hali Magazine , Issue : 146 – 2006

Prepared by : Zakariya Sheikh Kelo and Yaser Al Saghrji

==========================================

The Handmade Kilims in Afrin

Afrin is situated in the north-west of Syria . It was well-known, since the past, of manufacturing kilims. All the houses, in 350 villages spreaded in the mountains and plains, were considered to be factories that produced kilims (weavings) by a very simple loom (Tavna).

The skillful hands of the Afrinian women interacted with the colours, drawings and designs of the kilims. Only the housewives and young girls were the weavers and they always tried to be the best in making a high quality kilim which involved more time and great effort. They made various kinds of kilims and for different uses.

The people used kilims as coverlets, curtains and for decoration. Kilims were parts of nature in the houses because the mentality of women removed many aspects of nature into these kilims such as grapevines, roses, horses, slim-waist, olive trees, flies, birds and the colours. Nature was the resort of inspiration for those women who tried to imitate the Afrin attractive nature and the livings around them and produced very remarkable pieces of kilims. The loom (Tavna) which was as simple as the Afrin society produced colorful and different sizes of kilims. Though, it was consisted of some pieces of wood, it produced a very valuable narrow pieces of kilims which connected together after finishing the whole pieces. Afrin weavings have many beautiful kinds:

- Muhri is made of goat and sheep wool and without ornaments. There are just separated lines. It has natural colours.

- Cotton kilims are which and have separated colorful lines with or without ornaments .

- Ornamented kilims are the most common and made of sheep wool. They have different colours especially orange, red, green and yellow. They are full of designs.

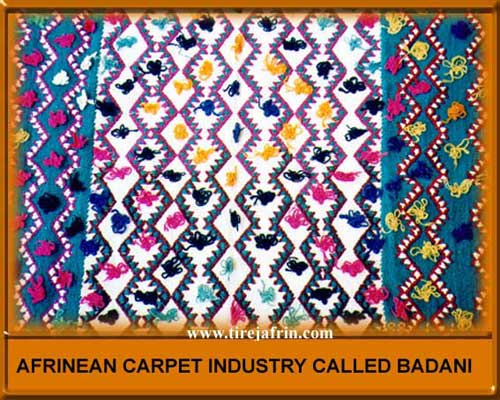

- Badaneh is very beautiful and it's very special. It consists of three "taj" - longand narrow pieces. It has the same colour in the sides and different one in the middle. It's very unique.

- Parda (curtain ) is also very magnificent for the occasion it made for. When a couple got married this kilim hanged in order to separate an open room as a kind of privacy for days, so it called "the bride curtain" . It had to be light, fine and full of cheerful designs and ornaments. It is the most expensive because it required skillful hands and more time to make it. There are many other kinds of these weavings and for many different uses and purpose. .

I'm very grateful to those women who dedicated their lives and times to develop their ways of life and to make use of everything around them. They played a great role in our society and worked side – by – side with men.

Unfortunately, these weavings disappeared since more than 25 years age, and I seek all the people who are interested in this to re-live it in order to enrich the memory of nations.

For more information, you can visit and contact:

Zakariya Sheikh Kelo, interested in the history and kinds of weavings in Afrin.